The gallery’s website was taken down and replaced with a note.

“It is with profound regret that the owners of Knoedler Gallery announce its closing, effective November 30, 2011. This was a business decision made after careful consideration over the course of an extended period of time. Gallery staff are assisting with an orderly winding down of Knoedler Gallery.”

No one answered the phone. The doors were locked. One of the most prestigious galleries that helped create and cultivate American art was finished, and it took the art world by surprise.

Born in Bavaria, Michael Knoedler immigrated to New York to open a branch for Goupil, Vibert & Company, a Parisian dealer he worked for at the time. He established Knoedler and Company in 1846 and attracted wealthy clientele from the California gold rush and the discovery of petroleum in Pennsylvania. By 1859 he was able to buy out Goupil and move his gallery to North Broadway. Not much is known about Knoedler himself, but he cultivated a reputation for his gallery and for American Art. Before his death in 1878, he brought his son, Roland, into the business to take lead; his other sons, Edmond and Charles, also joined later.

The rest of Knoedler’s history is extensive and romantic; the gallery is praised as being essential to the American art world and as an institution that represented great artists. However, as allegations of forgery and corruption taint its glorified history, Knoedler Gallery is also going to be remembered for its downfall.

Eight lawsuits have been filed by customers who claim they were fooled into buying forged artworks purported to be originals from the hand of modern masters like Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Richard Diebenkorn. As of August, two of these claims have been settled, one involving a Jackson Pollock action-painting purchased for $17 million.

Stories and articles detailing the accusations as they unfolded against Knoedler, and Knoedler’s response to those accusations, have been bouncing around since the gallery shut their doors in November, 2011. Boiling down all the moving parts and players leaves: Ann Freedman – Knoedler’s former gallery director, president and 31-year employee who resigned in October of 2009; Julian Weissman – a dealer in his own right who worked for Knoedler in the 1980’s; Glafira Rosales – a dealer from Long Island; and Pei-Shen Qian- a 73 year old immigrant from China and struggling artist.

There are a lot of pieces to the puzzle, more than 60 drawings and paintings in question and over $80 million spent on them, but when looking past the trees to see the forest it is all pretty straight forward. Glafira Rosales found Pei-Shen Qian in Queens and paid him to paint fakes for her (only a few thousand dollars for each piece). She then took those fakes to Ann Freedman at Knoedler Gallery or Julian Weissman and, over a period of 15 years, sold them as newly discovered works.

Rosales claimed she obtained the majority of the paintings from a collector who did not want to be named. This collector, later referred to as “Mr. X” or “Secret Santa,” supposedly inherited the artwork from his father. Throughout this ordeal Knoedler gallery, Ann Freedman and Julian Weissman have repeatedly stressed they never doubted the authentication of the artworks provided by Rosales. Even without documentation of provenance, they always believed the pieces to be authentic.

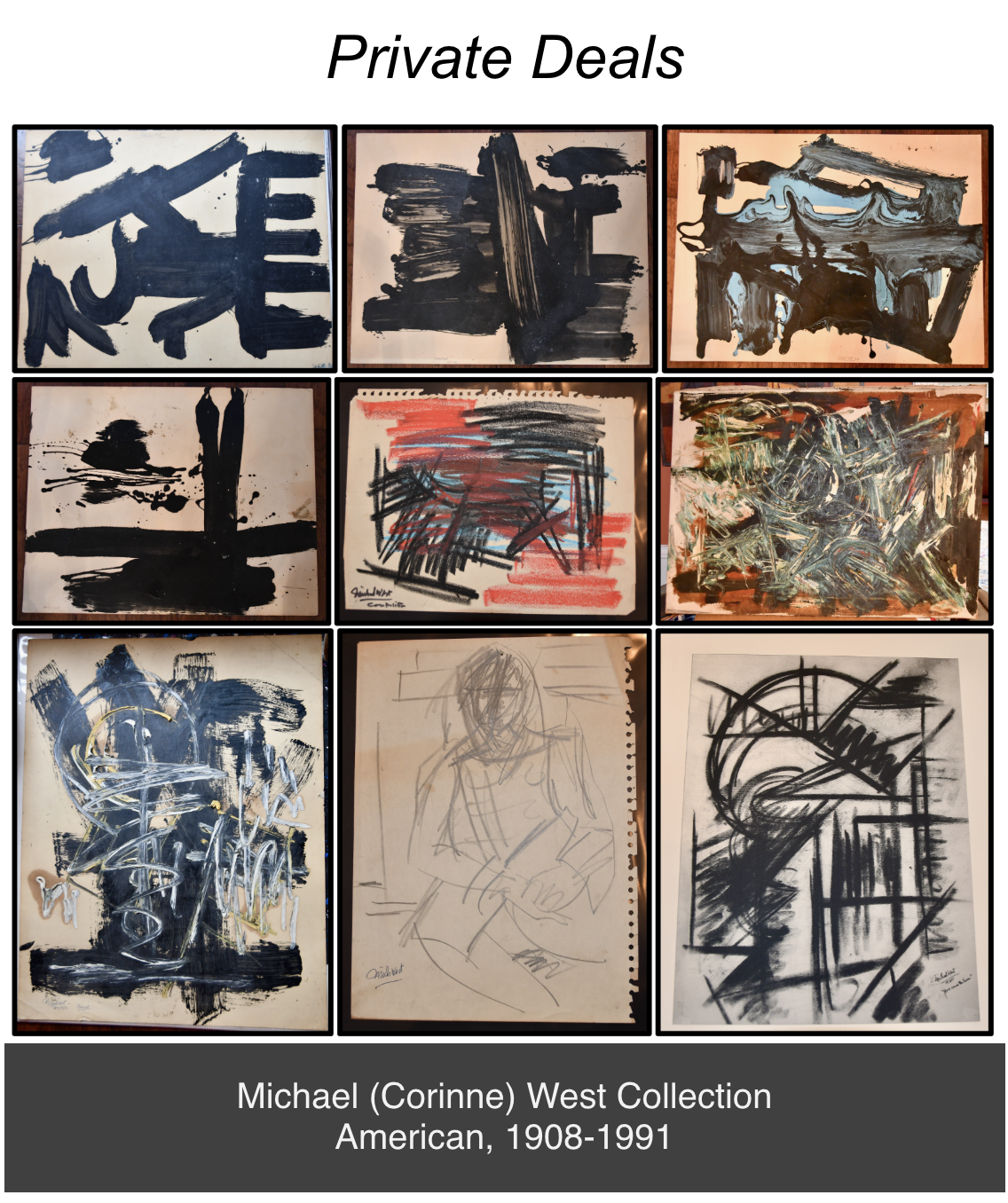

The civil lawsuits filed by collectors claim Knoedler Gallery, Ann Freedman or Julian Weissman sold them fake Abstract Expressionist artworks that Glafira Rosales provided. It is now known all the paintings were done by Pei-Shen Qian in the style of well-known Abstract Expressionist masters, and the thing is – they were well done. There is a high skill level behind Qian’s trained hand. He was able to study, master, and replicate the techniques and individual nuances associated with each artist he copied. His fakes, purported to be and marketed as authentic originals, flew under the radar and passed initial sniff tests by experts; for the first few years there was no suspicion, nothing that raised red flags or caused concern.

It wasn’t until 2009, when several Robert Motherwell works were questioned and investigated by the F.B.I., that the bubble burst. Rosales was arrested and released on a $2.5 million bond as she awaited trial for the criminal charges brought against her, and, so far, she is the only person being criminally charged. Her trial was scheduled for Monday, September 16. Ann Freedman has brought two defamation of character suits as of this September, claiming several news outlets did not do due diligence in reporting the experts she consulted regarding authenticity on a number of paintings. Mr. Qian, the man behind the “Secret Santa” and “Mr. X” monikers, has since fled to China.

It was recently reported that Freedman sold 40 counterfeits and Weissman sold 23; clients who purchased the fakes Rosales provided are suing both Freedman and Weissman in civil court. The U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York released a statement stating Rosales earned $33.2 million selling the forgeries to the Manhattan galleries through Freedman and Weissman; the galleries then sold the Rosales fakes and profited over $47 million total.

The dust is settling as much of the media hyped ‘forgery in the art world’ moves from the gallery to the courtroom.

But what of the value of forgery? Who is to blame, really?

Many responses to Knoedler Gallery’s involvement in the long-running fraud mock the art world, asserting if experts and collectors can be fooled it’s their own fault. Likewise, praise is brought to Rosales and Qian for swindling millions of dollars out of the hands of those elite who could afford to buy and invest in such property. This response, letting the rich endure the consequences of their privileged investments, comes up in the debate of forgeries; especially when the forgeries have passed the tests of experts and allowed the thieves to profit.

Make no mistake – they are thieves. People like Wolfgang Beltracchi, Ken Perenyi, John Myatt, and Han van Meegere (to name a few) are crooks. They create a product, create a story surrounding it, or, in some cases, fabricate provenance materials; then, profit off those they are able to fool. Like the Rosales-Qian team, these forgers were skilled and conniving, able to deceive and trick the eye in order to cash-in.

So why is there a portion of the public who cares not for the losses suffered by collectors and investors? Why is art fraud considered by the public as different from other forms of fraud, even though real people suffered? Honestly, it beats me.

I mean, OK, I get it – the average family working to keep debt at bay and a roof over their heads doesn’t have much sympathy for the guy who loses a few million on a forged painting. But, it makes no sense for the forger to be portrayed as a Robin Hood with a paintbrush. It is illogical to assert the mindset that, ‘the rich got what they deserved’ by purchasing or investing in artwork that turned out to be fake.

The wheels of justice turn slowly, but at least this fraud ring has been found-out. As of 1:24 p.m. this last Monday, Glafira Rosales pleded guilty to all nine counts brought against her, including wire fraud, filing false tax returns and money laundering, that she faced in connection with the ongoing investigation of the sale of forged works of art by the now-closed Knoedler gallery. When asked by the judge to explain why she is guilty Rosales admitted to, “falsely represented authenticity and provenance” on works sold to Knoedler Gallery and Julian Weissman Fine Art as being works by abstract expressionists including Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell. She confessed the works were “actual fakes created by an individual residing in Queens.”

She faces up to 99 years in prison, though her sentence is likely to be far less, and $81 million in restitution. She is free on bail and will officially be sentenced in March of 2014.

Greed will make people do crazy things. Rosales will likely spend the rest of her life in prison. But that cannot undo the damage she has done. Her actions shut down one of the longest running art galleries in American history, cost many people their jobs, soiled the reputation of several dealers and experts in the art world and cost real people real money and anguish.

So, the value of forgery?

Forgery involves an intention to deceive others about a work's history, and for Glafira Rosales the value of forgery came down to facing a maximum of 99 years in prison and 81 million dollars to make amends for the damages she caused.

That's a stiff consequence but the art world will be sorting out the damage she has done for many years to come.

-M.P. Callender

Recent articles on the case

New York Daily News The New York Times Art Daily Art Market Monitor

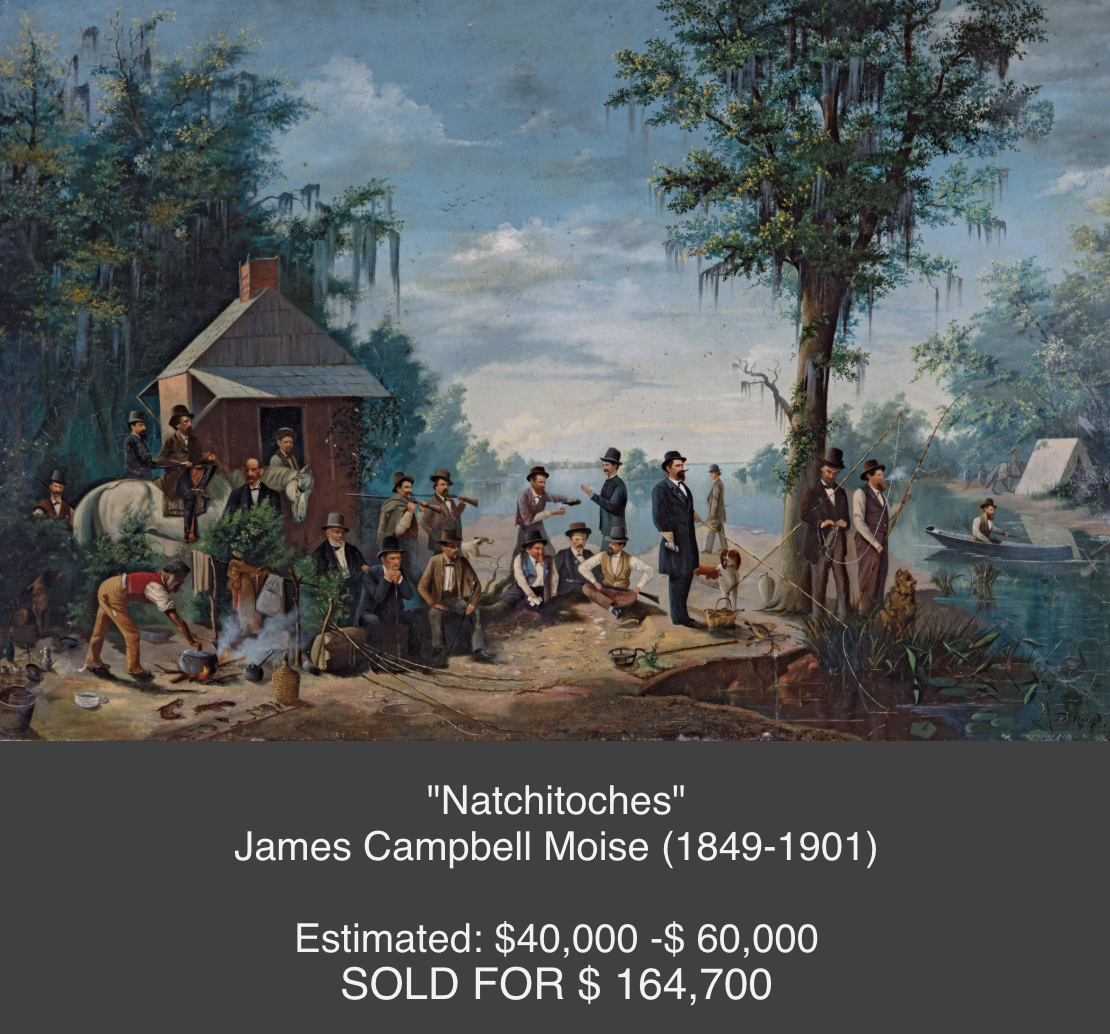

Research and be hands on: Don’t be afraid to approach the auction world if it is something you are interested in and something you are able to devote time to. It can be loads of fun. Just do not dive into it without knowing what you are getting into. Go preview and watch an auction. Dallas Auction Galleries and Heritage Auctions are great places to start here in the DFW area – make a fun evening of it. Watch live auctions going on all over the world through LiveAuctioneers to get some exposure before you register for a bidding paddle with your number on it.

Research and be hands on: Don’t be afraid to approach the auction world if it is something you are interested in and something you are able to devote time to. It can be loads of fun. Just do not dive into it without knowing what you are getting into. Go preview and watch an auction. Dallas Auction Galleries and Heritage Auctions are great places to start here in the DFW area – make a fun evening of it. Watch live auctions going on all over the world through LiveAuctioneers to get some exposure before you register for a bidding paddle with your number on it.

"Society Portraits" (2008) - Huge color images show the struggle of status-obsessed culture, women with mounds of makeup and cosmetic alteration clinging to youth. In these Sherman makes her characters vulnerable behind all the costuming and make-up, commenting on society's perception and intense focus on beauty.

"Society Portraits" (2008) - Huge color images show the struggle of status-obsessed culture, women with mounds of makeup and cosmetic alteration clinging to youth. In these Sherman makes her characters vulnerable behind all the costuming and make-up, commenting on society's perception and intense focus on beauty.

"History Portraits" (1988–90) - A modern representation in Art History, highlighting the relationship between the painters and their model, with allusions to Ingres, Caravaggio, Raphael and other Old Masters; all who were men, all whose models were women. Sherman borrows from several periods of art, renaissance, the baroque and neoclassical. The artist uses heavy makeup and obvious prosthetics to transform into the characters of the era.

"History Portraits" (1988–90) - A modern representation in Art History, highlighting the relationship between the painters and their model, with allusions to Ingres, Caravaggio, Raphael and other Old Masters; all who were men, all whose models were women. Sherman borrows from several periods of art, renaissance, the baroque and neoclassical. The artist uses heavy makeup and obvious prosthetics to transform into the characters of the era.

"Fashion" (1983–84, 1993–94, 2007–08) - This is a series of works that challenge and comment on ideas of beauty and grace within the fashion industry. Over the years, fashion has been an inspiration for Sherman and she has been commissioned by many well known fashion designers and magazines.

"Fashion" (1983–84, 1993–94, 2007–08) - This is a series of works that challenge and comment on ideas of beauty and grace within the fashion industry. Over the years, fashion has been an inspiration for Sherman and she has been commissioned by many well known fashion designers and magazines.

"Centerfolds" (1981)- A series of twelve images that refer to the printed page and the cinema in two by four foot horizontal photographs where the female subjects are placed on differing emotional stages; scared, lonely, melancholic, bored, heartbroken. Here Sherman is exploring the alienation of women. A great work in this section, "Untitled #96, 1981", in which Sherman lies on a linoleum floor in a sweater and skirt looking absently away from the viewer, a thirty-something single clutching a personals ad torn from a newspaper, sold at a Christie's New York auction for $3.89 million in 2011, the most expensive photograph ever sold at the time (a record which has since been beaten).

"Centerfolds" (1981)- A series of twelve images that refer to the printed page and the cinema in two by four foot horizontal photographs where the female subjects are placed on differing emotional stages; scared, lonely, melancholic, bored, heartbroken. Here Sherman is exploring the alienation of women. A great work in this section, "Untitled #96, 1981", in which Sherman lies on a linoleum floor in a sweater and skirt looking absently away from the viewer, a thirty-something single clutching a personals ad torn from a newspaper, sold at a Christie's New York auction for $3.89 million in 2011, the most expensive photograph ever sold at the time (a record which has since been beaten).

"Clowns" (2002–04)- All of the subjects in this series are dressed in bright colors and carnivalesque makeup, a jovial and even comical surface layer for the characters. Sherman is using the clowns because, underneath the vibrant bursts of color and wide tooth smiles, is an underlying sadness. As the artist said in an interview last year, "clowns are sad, but they’re also psychotically, hysterically happy." Sherman is using the persona of the clown to have a conversation - people can paint themselves to look happy, even if they are sad underneath. She goes to the extreme to show the vast emotional possibilities behind a painted smile.

"Clowns" (2002–04)- All of the subjects in this series are dressed in bright colors and carnivalesque makeup, a jovial and even comical surface layer for the characters. Sherman is using the clowns because, underneath the vibrant bursts of color and wide tooth smiles, is an underlying sadness. As the artist said in an interview last year, "clowns are sad, but they’re also psychotically, hysterically happy." Sherman is using the persona of the clown to have a conversation - people can paint themselves to look happy, even if they are sad underneath. She goes to the extreme to show the vast emotional possibilities behind a painted smile.

"Sex Pictures" (1992)- After the popular success of her "History Portraits" show, Sherman felt she had to challenge herself to do something difficult, something that would make it "...hard for the audience to just, you know, applaud and throw their hands up in the air..." she said in a 2010 interview when asked about her jarring new series. Reenacting pornographic scenes with prosthetics and mannequin parts purchased from medical-supply catalogues, this section of the exhibition should have a warning sign to caution parents from bringing their children in. The images are graphic, sexual, and though there is no actual nudity since everything is fake, the photographs

"Sex Pictures" (1992)- After the popular success of her "History Portraits" show, Sherman felt she had to challenge herself to do something difficult, something that would make it "...hard for the audience to just, you know, applaud and throw their hands up in the air..." she said in a 2010 interview when asked about her jarring new series. Reenacting pornographic scenes with prosthetics and mannequin parts purchased from medical-supply catalogues, this section of the exhibition should have a warning sign to caution parents from bringing their children in. The images are graphic, sexual, and though there is no actual nudity since everything is fake, the photographs  "Fairy Tales & Mythology" (1985)- “In horror stories or fairy tales, the fascination with the morbid is also, at least for me, a way to prepare for the unthinkable…That’s why it’s very important for me to show the artificiality of it all, because the horrors of the world are unwatchable and they’re too profound. It’s much easier to absorb – to be entertained by it, but also to let it affect you psychologically – if it’s done in a fake, humorous, artificial way.”

-Cindy Sherman

"Fairy Tales & Mythology" (1985)- “In horror stories or fairy tales, the fascination with the morbid is also, at least for me, a way to prepare for the unthinkable…That’s why it’s very important for me to show the artificiality of it all, because the horrors of the world are unwatchable and they’re too profound. It’s much easier to absorb – to be entertained by it, but also to let it affect you psychologically – if it’s done in a fake, humorous, artificial way.”

-Cindy Sherman

As a working artist, Sherman continues to use her own disguised body as the subject in her works. Her photographs are not self-portraits and have nothing to do with the artist herself. All of her works are untitled and simply given a number, i.e. "Untitled #109" or "Untitled #434", which further distances Sherman from the images; she wants the viewer to draw their own conclusions and has refused to title any of her works. Throughout her career, from the film stills to the society portraits, her work has been an investigation of identity - what it is, how we use it, how it changes - and how photography is the means in which identity is manufactured in popular culture and, now, social media.

As a working artist, Sherman continues to use her own disguised body as the subject in her works. Her photographs are not self-portraits and have nothing to do with the artist herself. All of her works are untitled and simply given a number, i.e. "Untitled #109" or "Untitled #434", which further distances Sherman from the images; she wants the viewer to draw their own conclusions and has refused to title any of her works. Throughout her career, from the film stills to the society portraits, her work has been an investigation of identity - what it is, how we use it, how it changes - and how photography is the means in which identity is manufactured in popular culture and, now, social media.