Regionalism is an art term coined in the 1930’s to describe the work of several modern realist painters whose work seemed to tell the story of their particular region of America. The term was originally used for mostly Midwestern artists. Regionalists never worked in a coordinated school or artists’ group. The term was used to describe the idiosyncratic works of such artists as Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry and Alexandre Hogue. I have always been a fan of regionalist artists. Like the Ashcan school (NYC-1910-20) and the Impressionists (Paris- late 19th C.) before them, the regionalists chose as their subjects the everyday people around them. Because the times in which these artists lived were times of great economic hardship, their paintings naturally gravitated toward portraying the anguish as well as the triumphs of real people. Though the intent of the work was not necessarily to press for social change, the art made strong statements about the suffering of people forced into poverty by the Great Depression and contributed to public sentiment about the need for change. It can be argued that FDR’s New Deal was aided greatly by the paintings done by regionalist artists in the 1930’s that clearly depicted the hardships of the time.

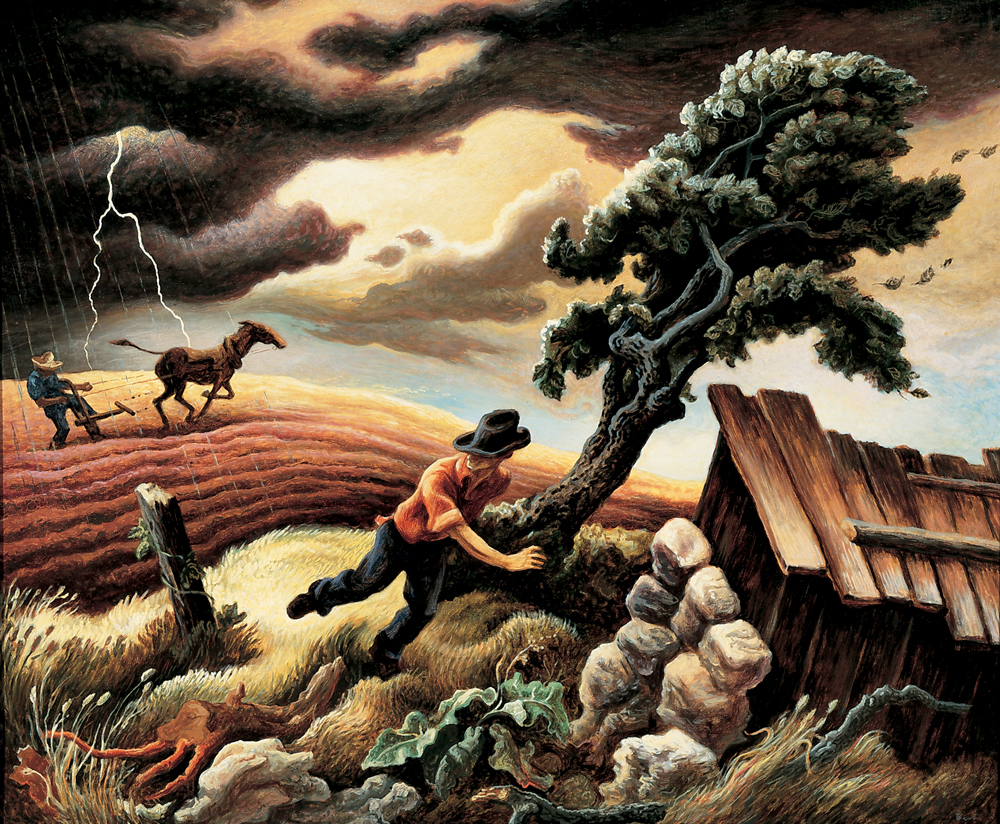

"The Hailstorm," Tempera on canvas mounted on panel, 33 x 40"

Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska

*This painting not shown in exhibition, depicted here to illustrate Benton's regionalist style

Benton was no backwater, untrained Midwesterner who chose his subjects because the Midwest was all he knew. He studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Academie Julien in Paris. He lived and worked in New York City for over twenty years. Yet he is best known for the regionalist works he began in the 1930’s when he declared himself “the enemy of modernism” and began a series of large-scale figural murals about American life and history. In 1932, Benton painted The Arts of Life in America, a set of eight large murals for an early site of the Whitney Museum of American Art. He won a commission for a series of murals about Indiana life to be shown at the 1933 Century of Progress Exhibition in Chicago. In 1935, he was commissioned to create a series of murals for the Missouri State Capital. It was in these large-scale mural works that his attenuated “El Greco-like” figures in overalls and prairie dresses became well known. He tackled both the heroic and infamous parts of the histories he portrayed. By the mid 1930’s, Benton was well known for such subjects. He had settled in Kansas City, Missouri and accepted a teaching position at the Kansas City Art Institute. To this day, what Benton is best remembered for are these iconic images of simple folk struggling to eek a living out of the land, trying to survive in the face of tornadoes, heat, drought and poverty.

"Hollywood," 1937–38, Tempera with oil on canvas, mounted on panel, 56 x 84"

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri

So, I was quite surprised to learn that he also had long-time ties to the film industry and a whole body of work influenced by Hollywood. The current show at the Amon Carter Museum addresses this heretofore unexplored area of Benton’s work. Benton first went to Hollywood in the summer of 1937, on assignment for Life magazine. He had, by that time, become quite well known for his large scale mural works and had had a self portrait featured on the December 24, 1934 cover of Time magazine. Benton was the first artist to be so featured. Life magazine wanted a full color spread about Hollywood to print. They sent Benton to Hollywood for a month. He was given fairly free rein at the studios and offices of 20th Century Fox Pictures for that month. He sat in on story conferences, watched filming of various movies, visited set designers, costume designers, interviewed producers, directors, cameramen and all the various workers on the sets and in the offices of a motion picture studio. Benton took an almost journalistic approach to the drawings he produced in this series. The end result in terms of artistic productions was a wonderful series of over four hundred graphite sketches, forty finished drawings of the various activities of the industry, a lithograph entitled “the Poet” and a large mural painting entitled “Hollywood” that amalgamated the production of several movies into one piece. This painting shows directors, camera men, actors, makeup artists and movies being made on several sets. It shows the mechanics of the industry and the extensive work behind the glamour.

Although Life magazine never published the article using Benton’s illustrations, the experience opened many doors for Benton in the movie industry. Directors and producers realized the value of using his images to promote their movies. Between 1939-1954 he was commissioned to create artwork for such projects as the John Ford directed movie adaptation of John Steinbeck’s “Grapes of Wrath,” John Ford’s “the Long Voyage Home” and the Burt Lancaster produced and directed movie “The Kentuckian.” Benton also illustrated many books during this era that were later turned into movies.

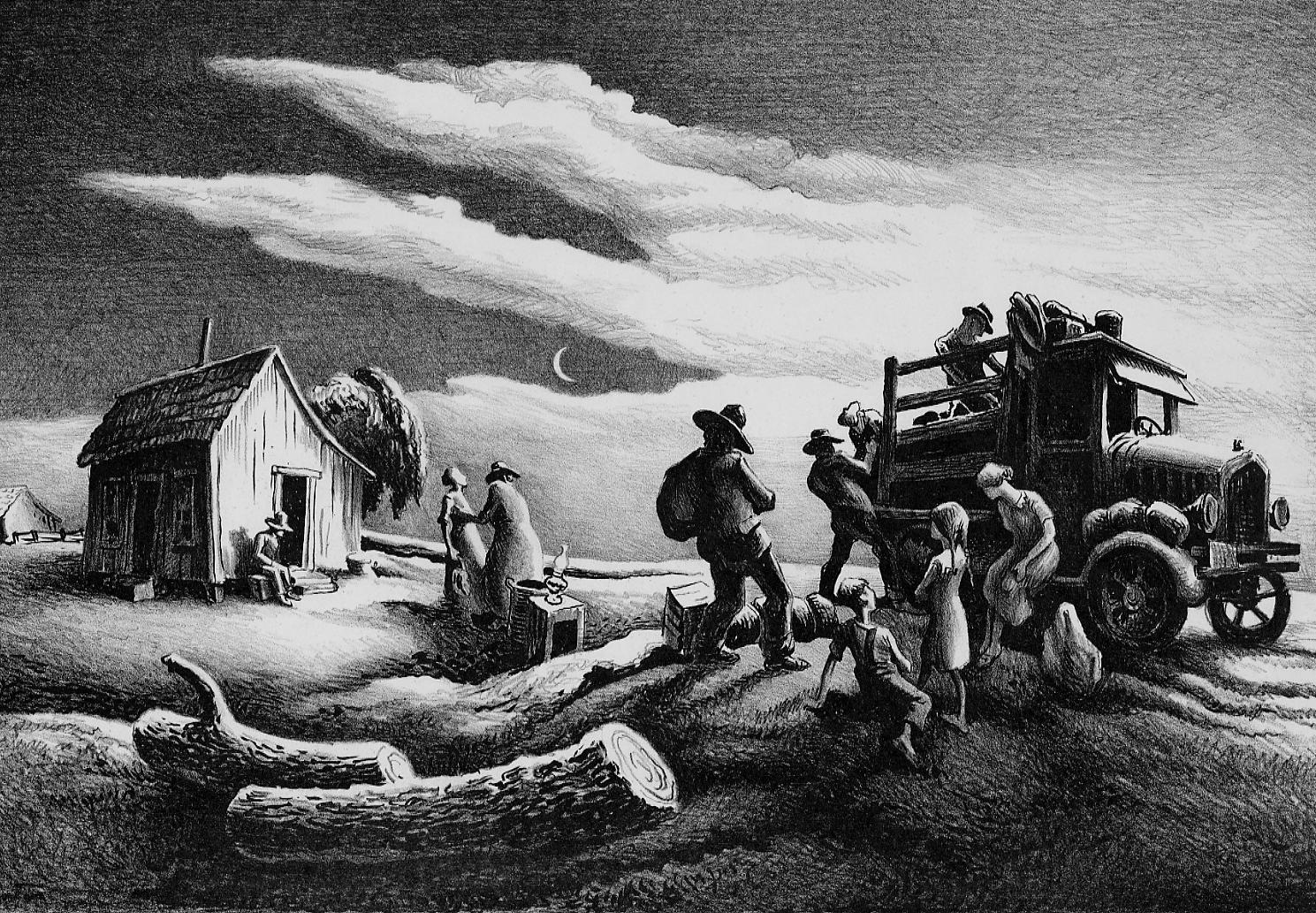

"Departure of the Joads. (The Grapes of Wrath Series)," 1939, lithograph, edition of 100, 12.75 x 18.25"

When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in December, 1941, it drew America into World War II. The U.S. War Department created many propaganda films during the war for the purpose of aiding the war effort. Benton did a number of propagandistic paintings during the war. For me, these were some of the most surprising and engaging paintings in the show. In 1942, Benton produced a series of seven propaganda paintings, the group collectively called “the Year of Peril.” These paintings are gut wrenching. They portray the Germans and Japanese as caricatured ethnic monsters intent on raping, pillaging and defiling America. The titles refer to biblical passages. In the painting entitled “Again,” Jesus’ body, here standing in for European and American cultures, is writhing on the cross as a German plane strafe bombs him and a large group of German and Japanese thugs plunge a spear into his side. Benton was very much a part of the war effort. Paramount News interviewed Benton in 1942 and films the exhibition of his “Year of Peril” paintings. In 1942, Benton also produced a painting entitled “Negro Soldier,” the intent of which was to address the contributions of African Americans who were serving in the segregated armed forces. This painting was not received well by the black community as the main figure in the foreground of the painting, a black soldier carrying a bayoneted rifle, was seen as caricatured. Looking at this painting and trying to accept that Benton meant for the man to appear heroic is difficult to do in contemporary times since our sensibilities about matters of race have changed radically in the intervening years. But, the painting is a good period piece and ought raise some important questions.

"Indifference, Year of Peril," 1944, Oil on canvas, 21 x 31"

State Historical Society of Missouri, Columbia

This show pulls together a large group (over 100 pieces) of Thomas Hart Benton’s work that had been previously ignored. The show gives a whole new view of his life’s work. There is even a section that addresses his working methodology. Benton often created dioramas of the scenes he wished to paint in order to have a three-dimensional model he could light and paint. There is a hands-on section that allows guests to move figures around and play with lighting in order to better understand Benton’s methods.

The show is incredible and, as are all shows at the Amon Carter, free to the public. Take the time to come for a visit. And, if you have never taken the time to appreciate the rest of the Amon Carter’s collection, plan several hours and immerse yourself in American Art. For all of my appraisal colleagues who are members of the International Society of Appraisers are coming to Fort Worth in mid-April for this year’s conference, this should be on your must do list. I believe the preconference tours will be covering the Amon Carter. But if you cannot come in early, stay an extra day and take in this show! It is a short taxi/uber ride from downtown to the Fort Worth arts district. You will find the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in close proximity to the Kimbell Museum and the Modern.

-Brenda Simonson-Mohle, ISA CAPP